Behind the Wheel With: Robert Klara

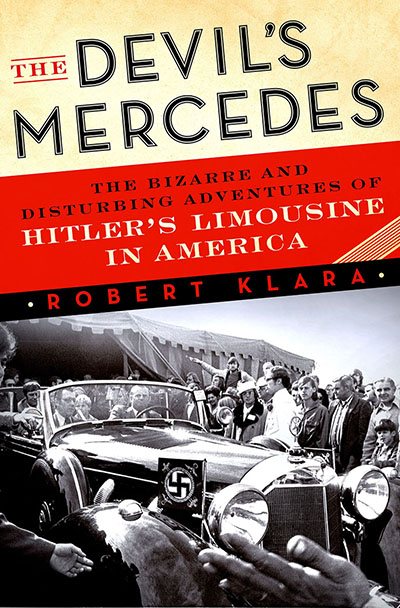

Robert Klara is the author of the critically acclaimed FDR’s Funeral Train and The Hidden White House. His unveiling of the private world of the famous funeral train was hailed as “a major new contribution to U.S. history” by Douglas Brinkley. His second book, a dramatic account of Truman’s fight to save the White House, was called “popular history at its best” by the Christian Science Monitor. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, among other publications. His latest book, The Devil’s Mercedes: The Bizarre and Disturbing Adventures of Hitler’s Limousine in America, is just hitting shelves now and it is nothing short of fascinating. It’s the story of the Mercedes-Benz Grosser 770K touring cars used by Hitler and other leaders of the Nazi party during World War II. Two were brought to the United States following the war and put on display, drawing huge crowds wherever they went. The cars changed hands often over the years, in some cases making their owners’ lives miserable.

It’s an intriguing story and one that’s masterfully told by Mr. Klara. We’ve published an excerpt here, and you can purchase The Devil’s Mercedes here. We had a chance to ask Mr. Klara a few questions about the book and his fascination with cars, trains and all things mechanical.

What inspired you to take on “The Devil’s Mercedes”?

I wanted to find a true story about an automobile believed to be cursed—a car with a sinister past, and how that past influenced the lives of the car’s new owners. I cycled through the usual suspects (such as the Graf and Swift double phaeton that Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in) and found little that was new, credible, or interesting. And then the idea hit me: What sort of car did Hitler drive around in? Having discerned that the W150 Grosser 770K Mercedes was his favored automobile, and that he had quite a few of them at his disposal, the discovery that a few of these cars had actually found their way to America in the days after the war furnished me with an irresistible story to investigate. Things essentially unfolded from there.

Besides the infamy of the original owners of the Grosser 770K Mercedes limousine, what is the most impressive thing about them to you?

I was taken by the sheer size and styling of these cars. From the very beginning, they were contemplated to be far more than mere transportation. The armored Grossers also served to protect Hitler from would-be assassins’ bullets and roadside bombs and, perhaps most significantly, the limousines played a central and carefully orchestrated role as propaganda machinery. The impressive but fearsome rallies that the Nazis held in Nuremberg invariably involved motorcades with senior officials riding in them. The Mercedes Limousines were used to accentuate the sense of power and control that Hitler exercised over the country. In their exaggerated, overbearing appearance, they were intimidating automobiles—and they’d been designed to be exactly that.

What do you think the lesson is from these two cars that made their way to North America with one spending so much time on display in post-war America and the other in Canada in a museum that ultimately did not want it, but chose to keep it?

Well, aside from the over-arching lesson that nobody like Hitler should ever be allowed into a position of influence ever again, the central lesson to me was that artifacts such as these cars remain enormously potent symbols of an immense historical tragedy and, as such, people who own those artifacts need to be careful in how they use them. The book demonstrates that Hitler’s car, by dint of its dark past, never lost its power to draw many onlookers curious to see it—even decades after the war ended. Which means that, along with the cars, there exists an opportunity to educate and inform the public about the war, the demagogue who started it, and the human-rights catastrophes that he unleashed. Fortunately, both of the Nazi limousines in this book are now in the hands of people who understand and appreciate the cars’ symbolic power, and the responsibility to use it for constructive ends.

Now to questions about you and your cars, what kind of car did you learn to drive in?

The first car I drove on my own was my father’s 1972 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. It was, I think now, perhaps a bit of foreshadowing of my interest in huge and decadent automobiles, since the Cadillacs of that era were simply enormous—ruinously so, given what the oil embargo of the later 1970s would do to Detroit. But yes, I drove the Caddy up the hill where we lived, and still remember those electric seats and power steering so loose you could move the wheel with one finger. I didn’t last long on the car, though, and I could never parallel park it. Fortunately, my dad bought me a 1982 Honda Accord—a little four-banger with a 5-speed manual transmission—and it was much easier and more fun to drive.

What do you drive now?

Believe it or not, nothing. I live in New York City, and having a car there is impractical. We have 722 miles of subway in New York, and I am grateful every day for the engineers who built them. Even so, I do miss driving. I miss the time in my life when driving was part of how I socialized.

You do some travel writing, do you like to take road trips?

I hope this response doesn’t constitute sacrilege, but I really don’t. I have a preoccupation with big things that move—old cars, ships, and especially trains. So when I go somewhere, I try to take a train, even though that means putting up with the vagaries of Amtrak. Other times I fly, and let someone else do the driving. If I’m in the back seat, I can read, and road rage isn’t my problem.

What would be your ultimate road trip car?

I’m going to give you an utterly ridiculous answer, because my tastes have never been practical. But the car I’ve always admired most is the 1941 Packard 120 sedan. It’s a magnificent beast of a car, and I’m sure it would be a poor choice for any long-distance trip. But I’d like to take one of them down the Overseas Highway all the way to Key West. If I could sleep at Hemingway’s house when I got there, it would be perfect, but I doubt they’d let me.

What has been your favorite road trip?

A very dear friend of mine who’s since moved away from New York City—a man who shared my love for the post-industrial landscape—used to volunteer his beat-to-hell Toyota pickup truck for various adventures we’d take deep into Pennsylvania, where we’d seek out abandoned railroad structures (roundhouses, coaling towers, bridges, etc.) and explore them. We’d disappear on a whim, stopping at diners on the way down and back, and spend the day risking our lives climbing on things in the middle of nowhere. On one trip I recall, we drove down to Scranton so we could cross the abandoned Nicholson Viaduct on foot—which was a little crazy, but incredible. We slummed it in that drafty truck on that trip in the winter, but I’ve rarely had a better time on the road.

Where would you like to go and drive the back roads that you have not been to yet?

The Pacific Northwest. It’s the one part of the country I’ve never really spent time in. And the land is so varied, rugged, and beautiful. I’d happily get lost a few days in that part of the country.

And last, is there another historical automotive adventure book in the future for you?

I’m not sure. I might like to do another book about a car one day. But after spending three years on this one, I have a desire—first, to take a rest, and then to find a story about some other big and unusual thing that everyone’s forgotten about.

Thanks for joining us Behind the Wheel, Robert. And thanks for sharing the story of these disturbingly fascinating cars.